What is a synchrotron light source?

A synchrotron light source is like a Swiss Army knife, the ubiquitous multitool that many of us keep in our cars or pockets. At its core is the synchrotron itself, a type of particle accelerator that produces intense beams of light – typically X-rays – that researchers use to peer deep beneath the surfaces of things and explore a phenomenally wide range of scientific issues, from how a drug may stop a virus in its tracks to the chemical composition of an unknown substance or the microscopic structure of a new material. SLAC’s Stanford Synchrotron Radiation Lightsource (SSRL) is one of four dozen in operation around the globe. Researchers from all over the world come here to study neurodegenerative diseases such as Alzheimer’s, why batteries fail and even the content of ancient religious texts, among many other things.

Synchrotron explainer

Watch this video for a simple explanation of what a synchrotron is and why there are 60 around the world today.

Olivier Bonin/SLAC National Accelerator Laboratory

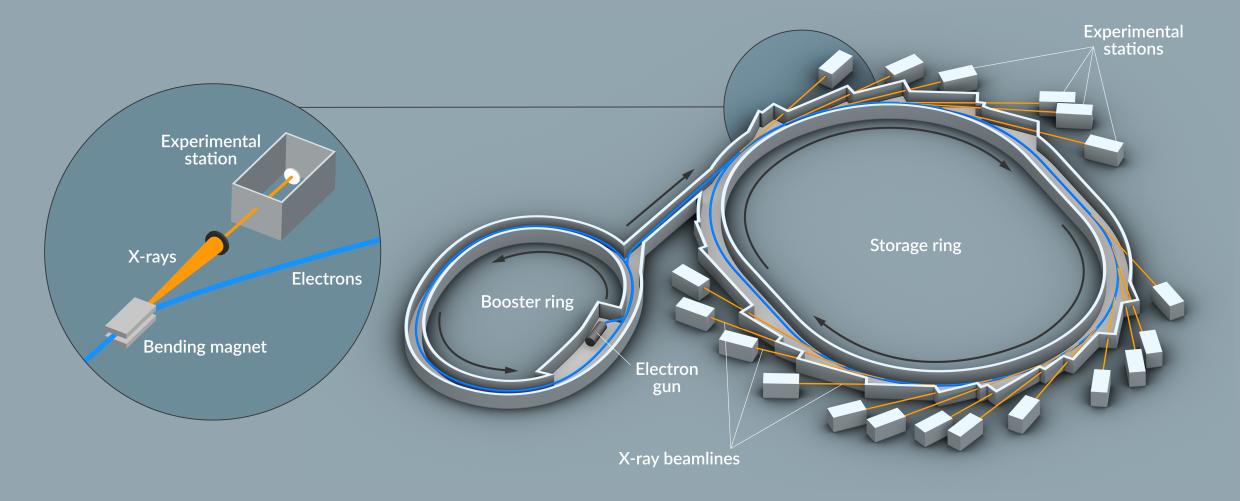

How does it work?

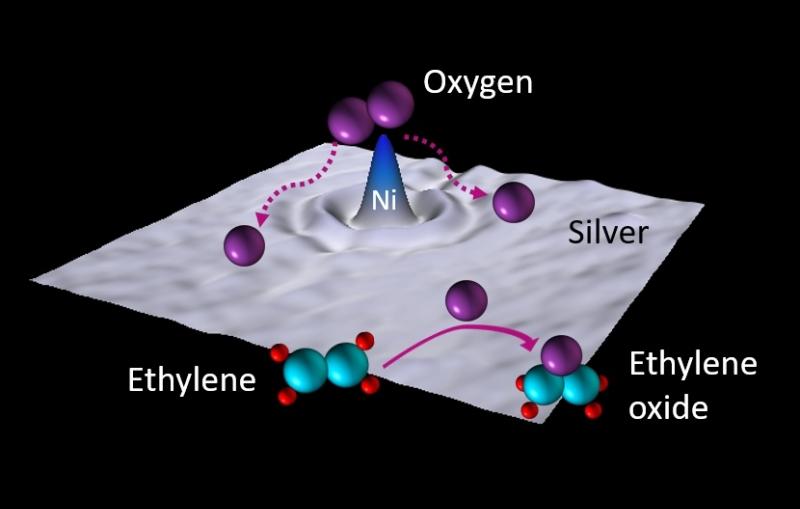

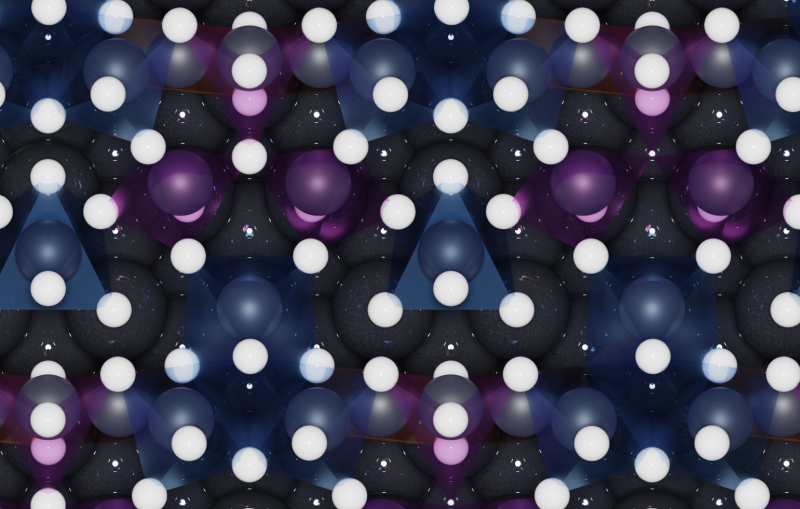

Synchrotrons accelerate charged particles, such as electrons, and keep them moving at more than 99 percent of the speed of light around a closed loop, often a circular ring. Any time charged particles change direction, they emit a cone of light, which is known as synchrotron radiation. At most synchrotrons this light comes in the form of X-rays. Often, electrons are forced to wiggle back and forth through special arrays of magnets called undulators, producing brighter X-rays.

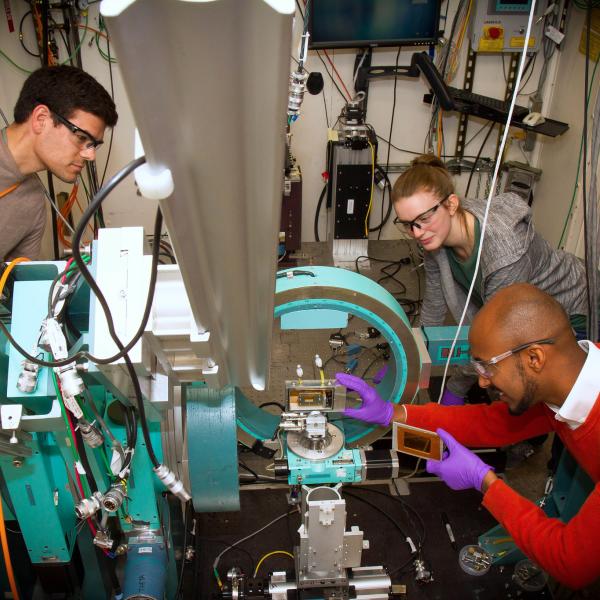

The X-rays are next focused into narrow and extremely bright beams, which scientists aim at samples of biomolecules, solar cell materials or even dinosaur bones. They can use a large and continually growing number of techniques to examine how the sample scatters, diffracts, absorbs or reemits the light, which reveals various different details of structure or chemical composition. Since each synchrotron has a number of beamlines, each with its own specialized instruments, a number of researchers can conduct a wide range of experiments using an equally broad range of techniques all at the same time.

What’s special about SSRL?

Every year, SSRL runs several thousand experiments for users who come to SLAC or participate remotely from their home labs. SSRL has 33 experimental stations and many full-time scientists who specialize in a wide variety of X-ray techniques that can image materials from the atomic to macroscopic scale – and who are here to help visiting researchers make the most of their experiments. Research at SSRL has contributed to more than 15,000 scientific publications since it began operating as the first high-energy X-ray user facility in the United States in 1974. It also led to the 2006 Nobel Prize in chemistry, awarded to Stanford Professor Roger Kornberg for revealing how DNA directs cells’ protein manufacturing.

How we use synchrotron light

Imaging biomolecules

The basic building blocks of biology – everything from viruses to human cells – are proteins, and X-ray studies have the power to reveal their molecular structure. This research enables us to better understand how our bodies work and how to fight disease.

Battery research

Making a rechargeable battery that can store plenty of energy and will withstand thousands of charging cycles is not an easy task. X-rays can help researchers understand how batteries degrade over time and how to create new materials and designs to make batteries last longer.

Solar cell research

Although solar cells have been around for decades, researchers have worked hard to make them more efficient. With the help of X-rays, scientists and engineers can understand how they work on a microscopic level, aiding the design of the next generation of solar cells.

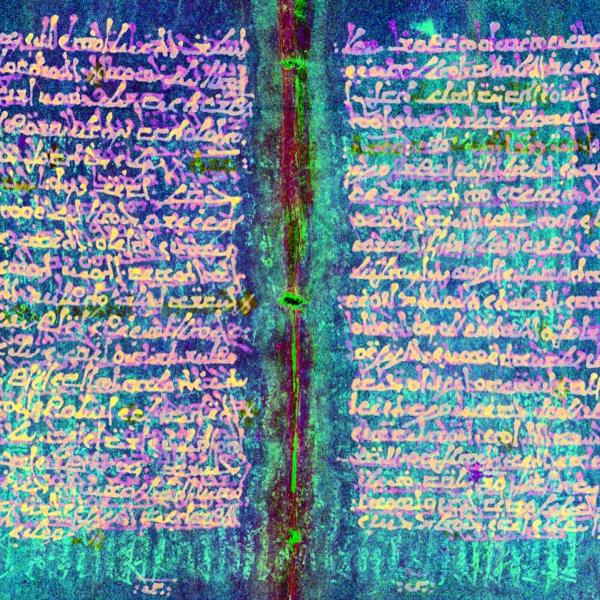

Cultural heritage and natural studies

Because different inks and pigments absorb X-rays in different amounts, researchers can shine a beam on everything from ancient parchments to read faded text, to fossilized dinosaur feathers to determine what color the creatures might have been.

Synchrotron science at SSRL

For questions or comments, contact the SLAC Office of Communications at communications@slac.stanford.edu.